Blog

Bidding on Democracy

I wrote a piece for The Drum at the end of last year in the lead-up to the UK election assessing the real impact of political advertising on social media. If the 2019 UK general election felt like a never-ending avalanche of misinformation and “fake news”, and even doctored videos, it pales in significance to what is taking place right now on the eve of the 2020 US election.

We are seeing the dismantling of fact as a construct of democracy with a tsunami of misinformation and “alternative fact” propelled upon millions of Americans through algorithmic and paid-for amplification. Just this week, in the days leading up to election day, Facebook had to remove ads from the Trump campaign giving voters the wrong election date in a bid to either confuse voters, promote early voting in key swing states, or to bypass Facebook’s recent rule of to restrict political advertising in the week before the election. Whichever is true this is the latest in a long, long line of incidents of the weaponisation of social media for political gain and with over 200,000 voters, in mostly swing states like Florida, Arizona, and Georgia having seen the ads it seems the political parties are winning at gaming a system which doesn’t seem too bothered about deterring it.

Democracy “at-risk”

Facebook recently announced that they have plans in place to counter any issues that may arise following the election whether that be in the hours following the closing of the polls or the weeks and months that follow. Placing the US as an “at-risk” country in which the platform can take measures to quell election unrest including lowing the spread of certain posts and changing what content appears and is promoted on users’ news feeds. This is a step the company has taken in countries such as Myanmar and Sri Lanka following civil unrest.

This follows steps Faceobok took earlier in the election cycle to ban political advertising in the days leading-up to the election and a ban they introduced in October on ads following election day. This post-election ban is currently for an indefinite amount of time with Facebook stating that they “plan to temporarily stop running all social issue, electoral, or political ads in the US after the polls close on November 3rd, to reduce opportunities for confusion or abuse”.

As I wrote in a blog post in early Oct, this is very much shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted. If Facebook were serious about tackling issues of voter suppression and even potential violent unrest following the election they would have acted much quicker and much more decisively. They could have taken action about limiting the spread of violent conversationss in Facebook groups as well as lowering the spread of certain posts and changing what content appears and is promoted on users’ news feeds.

12 Years in the Making.

It’s hard not to ask how we all got here and how the US became so exposed to this risk. As Vanita Gupta, the President & CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights stated we are seeing “unprecedented attacks on legitimate, reliable and secure voting methods designed to delegitimize the election”.

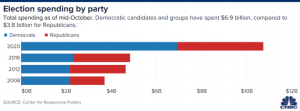

It seems crazy to think that just 12 years ago the idea that Barack Obama spent millions online during his presidential campaign was relatively new, with candidates online spending during that election totaling just $22.2 million according to Borrell Associates.

Fast-forward to today and the Center for Responsive Politics projects overall spending to more than double 2016 figures at a staggering $14billion with BIA Advisory Service estimating that online ad spend will make up 21% of overall spend (estimated to top $2.9billion across the election cycle). That’s a near-13,000% increase in online ad spend in just 3 election cycles! Cyrus Krohn, who famously wrote nearly 20 years ago at the birth of online advertising that “it might work too well”, said in a recent Guardian interview “the reason I said it might work too well is that mass marketing went away and micro-targeting – nano-targeting – came to fruition.”

This ability for political candidates to micro or nano-target individuals was exposed in the last US election most famously by Brad Pascale and the Trump campaign who spent a reported $1.4billion on online ads in 2016. Parscale claims to have 50,000-60,000 variations of Facebook ads every day during the 2016 campaign blitzing US voters newsfeed with persuasive messaging and misinformation with the ultimate aim of persuading undecided voters and having potential opposition voters stay at home. Pascale has since been made Trump’s 2020 re-election campaign manager cementing the belief that Pascale and others share that their approach to online advertising won the day in 2016 and took Trump to the White House.

It’s clear that online political advertising is no longer a rounding error in campaign budgets and Facebook has clearly taken some steps to curve their impact and influence. Google, another enormous recipient of political ad dollars, in the US and across the globe, has also taken steps to curve how political parties and campaign groups can target individuals in the lead-up to the US election. Though the search giant has managed to stave-off much of the media attention that has been directed at Facebook.

Zuck’s Misguided confidence

It seems we are too late to save this US election from interference. With the release just 100 days before polling of the nearly 1,000-page report into 2016 election interference by Russia, it made clear that more could be expected this time around. Not only that but the UK government confirmed back in July that they were “almost certain” that Russians sought to interfere in the 2019 UK election.

The cat is very much out of the bag in terms of foreign states using Facebook and Google and other online tools to interfere with the democratic process whether it is by wide-spread misinformation, attempts to suppress voting or campaigns aimed at discrediting individuals and campaigns. The tools of online amplification have been weaponised against us and with governments seemingly unwilling or unable to act to curb their online giants it is down to them to make significant changes for the sake of free and fair elections not just in the US and UK but across the world. Mark Zuckerberg said in a BBC interview back in May

“I feel pretty confident that we are going to be able to protect the integrity of the upcoming election.”

The company was heavily criticised for not curbing the Russian-backed interference with the Kremlin-directed Internet Research Agency (IRA) who between 2015 and 2017 flooded social media with false reports, conspiracy theories, and trolls, reaching a reported 126 million Americans in an attempt to swing the election for now-President Donald Trump.

Zuckerberg added, “One big area that we were behind on in 2016 but I think now we are quite advanced at is identifying and fighting this co-ordinated information campaigns, that come from different state actors around the world.”

Let’s hope Zuckerberg’s optimism isn’t as misguided as it seems.

Making a change

But, what could be done to make a change in the future?

Well, the first step would be for Facebook and Google to follow Twitter, Snapchat, and other platforms in banning political advertising. This would pour water on the fire of misinformation directly targeted at voters newsfeed in the months and weeks leading up to the election. The challenge from some is that this disproportionately affects those on a local level who rely on this targeted amplification to get their message out.

This is true but is a price unfortunately worth paying. Local candidates could invest the money they would have in advertising into building their organic audience online or utilising other cost-effective marketing channels. Banning all political advertising on these platforms may seem like an extreme step but we need to take some drastic measures to get the dangerous spread of misinformation under control. The system has been manipulated and the consequences of this for voters and the safety of a functioning democracy had never been considered when the ad platforms and their incredible pin-point targeting had been conceived.

An alternative, lighter step, would be to ban all non-official political campaign advertising. This would mean that only the candidates and politicians themselves and the teams running their campaigns from official pre-approved accounts could run ads. This would stop campaign groups from investing heavily in campaigns online a huge issue around misinformation and negative online advertising. This half-measure would stop foreign interference into elections and ensure only those messages seemingly approved by the candidate would be promoted. For many, this doesn’t go far enough but would still be a step in the right direction and something that seemingly Facebook and Google could instigate without much difficulty.

A final alternative would be to reduce the targeting capabilities for any political advertising. This less drastic approach could still have an impact on the highly efficient mass persuasion campaigns that we have seen developed in the US, UK, and across other countries to persuade undecided voters and even prohibit opponent supporters from voting. Providing limited targeting options, potentially just location-based targeting would mean that campaigns have less ability to individually influence voters and ensure they can’t specific target micro-groups based on specific fears or emotional traits exhibited by actions they have previously taken (how long they watched a video for or whether they engaged with a specific message).

All three options are technically possible as we’ve seen with the actions the platforms have taken in the days leading up to and beyond this tumultuous US Presidential election but it remains to be seen if there is the political will in DC and amongst the Silicon Valley tech elite to make these changes lastly.

But in the end, our sense of democracy and of free and fair elections may depend upon it.

Tom Jarvis – Founder & CEO